One hundred and twenty five years ago, on the night of July 22, 1893, law and order broke down in Memphis. A mob of several thousand attacked the jail; meeting almost no resistance from officers, they seized Lee Walker, a young African American man. The mob dragged Walker from his cell, beating him, stabbing him, and stripping him of his clothing. They took Walker north on Front Street to an alley between Sycamore and Mill Streets, where they hanged him from a telegraph pole. Once Walker was dead, many spectators left, but some mob members cut the body down, burned it, and mutilated it for souvenirs. As a final insult to decency and to the law, the mob members left the remains of Walker’s body at the courthouse. These remains were later gathered and buried in a potter’s field.

Walker was suspected of the attempted rape of a young white woman in northeast Shelby County near Bond Station. What occurred in that encounter is unclear. It is also uncertain that Walker was the man involved. Walker was arrested several days later near New Albany, Mississippi. If he were the man involved, he avoided multiple posses that began an immediate search, while walking nearly 90 miles across country barefoot. Neither the alleged victim nor her sister, who witnessed the encounter, were ever given an opportunity to identify Walker.

These grounds for doubt did not deter the Memphis press from launching viciously racist attacks on Walker, calling him a “monster,” a “negro fiend,” a “black brute,” a “negro ravisher,” a “man-devil,” and a “degraded scoundrel,” among other terms. The Memphis press also predicted that a lynching would be the result of his capture. The Public Ledger ran a large headline: RIPE FOR A ROPE.

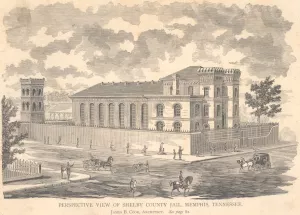

Walker should have been safe in the Shelby County jail, but the sheriff ordered his men not to resist the attackers. For this failure to do his sworn duty, the sheriff was indicted, along with a deputy sheriff, two police captains, and several suspected mob leaders. This attempt at restoring the rule of law failed, however, because it was impossible to seat a jury to hear the case. Only one juror out of a panel of 500 was found competent to serve, most of the others having formed a fixed opinion. One prospective juror stated that he thought the sheriff should receive a gold medal. The prosecutor gave up his attempt to hold a trial and no one was ever convicted for the lynching.

Walker was failed by law enforcement that did not protect him, by the press that vilified him, by the courts that were unable to prosecute his killers, and by the white public that tolerated the extra-legal killing of a black man on the mere suspicion that he had attempted an attack on a white woman.

In April of this year the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in Montgomery, Alabama to honor all the 4,500-plus lynchings that occurred in America between the Civil War and 1950. The memorial houses over 800 metal columns hanging from the ceiling, one for each county where a lynching occurred. Shelby County is among them. With 35 known lynchings we have more than any other county in Tennessee.

Why does this matter 125 years later? Shouldn’t we forget the past and “move forward”? Increasing numbers of Memphians are joining leaders and other citizens from cities all across the nation with a resounding “no!” Why? Because no community can heal from past wounds without facing them; Because no understanding of history can take place if any of the history remains buried; Because the horrors of racism continue in so many ways today; And especially because in this city where so many of us practice our faith weekly, all of our religious faith traditions call us to truth, justice and the hard, good work of learning to understand and love one another.

At 7 p.m.this Sunday, July 22nd, on the 125th anniversary of the lynching murder of Lee Walker, there will be a public, interfaith prayer service in his memory near the sites of the lynching and the old jail at the corner of A.W. Willis and Front St. Participants in the service will include Rabbi Sarit Horowitz of Synagogue Beth Shalom, Imam Hamzeh Abdul-Malik of the Midtown Mosque, Rev. Virzola Law, Lindenwood Christian Church, African ritualist and storyteller Ekpe Abioto, Soloist Madelyn Strong Woodley, Judge Carolyn Blackett, Tim Good of the National Park Service and others.

The service will include the dedication of a historical marker jointly sponsored by the National Park Service, the Shelby County Historical Commission and the Lynching Sites Project of Memphis. All are welcome. We hope you will join us.

Johh Ashworth, Executive Director and Rev. Canon Laura Gettys, Board President